Co-operatives in New Zealand

Extract from the The Four Pillars of Governance Best Practice

-

- Co-operatives are a major part of New Zealand’s economy.

- There are various types of co-operatives and a range of co-operative legislation in New Zealand.

- Co-operatives have unique features including operating in accordance with co-operative values and principles with a focus on members’ needs.

- Getting the right mix of skills and experience on co-operative boards can be challenging due to the elected model and narrower pool of potential board members.

Overview

Co-operative business models are common around the world and they form a major part of New Zealand’s economy. Some of the country’s largest and most successful organisations are co-operatives, supporting both urban and regional New Zealand.

The International Co-operative Alliance defines a co-operative as “an autonomous association of persons united voluntarily to meet their common economic, social, and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly-owned and democratically-controlled enterprise.”[1]

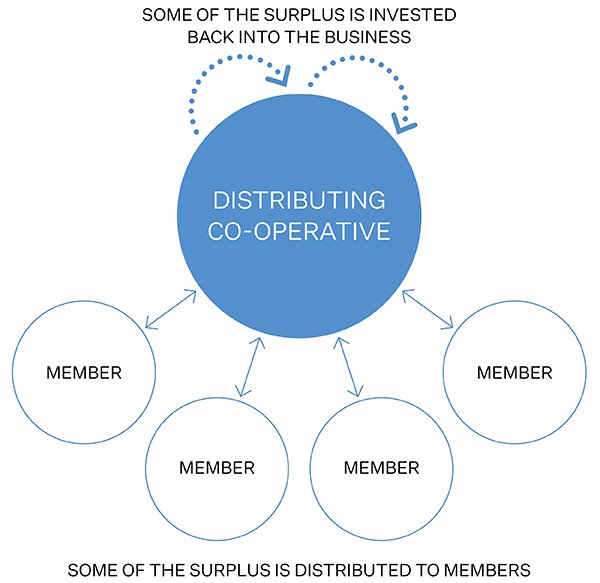

A key distinguishing feature of co-operatives is that their principal business is trading with their members (owners) who benefit through returns based on patronage, rather than investment. The following diagram illustrates the investment and distribution of surpluses (used with permission from the Business Council of Co-operatives and Mutuals).

Co-operatives are often established as a result of a market imbalance or adversity where a small group (eg of producers, customers or employees) collaborate to achieve economies of scale such as in negotiating terms and sharing costs. The model is adaptive to members’ needs and focused on long-term sustainability of the business which guides their strategy.

The co-operative economy in New Zealand

-

- New Zealand’s top 30 co-operatives’ total gross revenue represents approximately 20 per cent of the country’s GDP.

- Members form a significant proportion of New Zealand’s SME community (eg farmers, retailers, and service industries).

- Over 50,000 people are employed by co-operatives (this excludes employees of the members themselves).

- New Zealand’s co-operatives sit across multiple sectors, but they are primarily in agriculture and food.[2]

Types of co-operatives

Widely-recognised types of co-operatives include:

|

Producer |

Producer co-operatives are owned by people who produce similar types of products, eg farmers (growing crops, raising cattle for meat, milking cows), craft workers and artisans. By banding together, co-operating producers leverage greater bargaining power with buyers. They also combine resources to more effectively market and brand their products. Examples include Fonterra, Tatua Dairy, Organic Dairy Hub, Marlborough Wine Growers, Market Gardeners, Alliance Group, and Silver Fern Farms. |

|

Purchasing/

|

Purchasing/shared services co-operatives are owned and governed by independent business owners that come together to enhance their purchasing power, lower their costs and improve their competitiveness and ability to provide quality services and products. They operate in all sectors of New Zealand’s economy and include some of the largest businesses in the country. Examples include Mitre 10, NZPM Co-operative, Ravensdown, Ballance, Foodstuffs, Paper Plus, and ITM. |

|

Financial services |

Financial services co-operatives belong to their members, who are at the same time owners and customers. They are set up as a bank, building society or credit union. Examples include SBS Bank, Nelson Building Society, NZCU Baywide. |

|

Insurance |

Insurance mutuals are owned entirely by those who take out policies. Surpluses are either used to reduce future premiums or rebated to policyholders as a dividend. Examples include FMG (Farmers Mutual Group) and Southern Cross Health Society. |

|

Consumer |

Consumer co-operatives are owned by people who buy goods or use services of the co-operative. Examples include MHV Water, LIC, Farmlands, and RuralCo. |

|

Worker

|

Worker co-operatives operate in all sectors of the economy. Workers own and are employed by the co-operative. An example is Loomio. |

|

Housing |

Housing co-operatives are a large part of Europe’s housing stock, filling the gap between social housing and private ownership. The properties are usually owned by the co-operative but controlled by the members (tenants). |

|

Platform |

Platform co-operatives are evolving models based on a centralised technology platform that members sign up that enable them to access various services. They are starting to become more prevalent globally. |

Co-operative legislation

Many co-operatives are co-operative companies, registered under the Companies Act 1993 and the Co-operative Companies Act 1996. Others are established under specific legislation set out below.

|

LEGISLATION |

OVERVIEW OF KEY ELEMENTS |

|

Building Societies Act 1965 |

Building societies provide financial services (such as mortgage advances for purchasing property) and customers are members. Building societies:

|

|

Friendly Societies and Credit Unions Act 1982 |

Friendly societies (such as Southern Cross Health Society) include societies formed to provide (either through subscription or donation) relief of maintenance of members and their families during sickness, old age or widowhood, and:

Credit Unions are owned by their members to provide savings and loan facilities and must have a common bond (eg geography or employment relationship), and:

Friendly societies and credit unions are regulated by the Registrar of Friendly Societies and Credit Unions. |

|

Industrial and Provident Societies Act 1908 |

An industrial and provident society usually consists of owners of SMEs who also continue to operate independently (but they become part of a larger entity for mutual benefit). They work (industrial) and receive benefits (provident) from the society. Examples include taxi-co-operatives. Industrial and provident societies:

Members cannot claim interest in shares exceeding NZ$4,000. |

|

Farmers’ Mutual Group Act 2007 |

Mutuals are commonly founded by the insurance industry. These are private companies whose ownership base is made up of their clients who are also the policy holders. Members of FMG are principally farmers or persons providing services to farms. They are entitled to receive profits based on income generated, distributed as dividends based on the amount of business they transact. |

|

Co-operative Companies Act 1996

|

Co-operative companies are established, owned and controlled by a group of individuals for the purpose of equitably providing them with mutual benefits arising from their activities/patronage, not from their investment. Any type of business where the owners are also the principal users (buying or selling) can operate as a co-operative. The advantage is the mutual bond between transacting shareholders and the special features (in the Co-operative Companies Act) relating to shareholdings that depart from the standard arrangements under the Companies Act.

|

The Financial Markets Conduct Act 2013 and the Financial Reporting Act 2013 are also relevant to co-operatives given the need to obtain funds from shareholders, issue product disclosure statements and make distributions/provide rebates.

Most co-operatives have to produce annual reports prepared in accordance with XRB Standards. Reporting and external assurance provides an extra layer to a co-operative’s social licence to operate. Although not mandated, many co-operatives are also starting to prepare sustainability reports.

See also the Four Pillars of Governance Best Practice 4.6 External reporting.

Good governance in co-operatives

Much of the guidance on governance throughout the Four Pillars is applicable to co-operatives (eg around strategy and risk). However, other governance principles are unique to co-operatives and distinct from investor-owned businesses - for instance, operating in accordance with the co-operative values and principles and ensuring member voice and engagement.

Values and principles

Values of self-help, self-responsibility, democracy, equality, equity and solidarity underpin co-operatives. They are also guided by the following core principles (known as the Rochdale Principles):

- Voluntary and open membership

- Democratic member control

- Member economic participation

- Member autonomy and independence

- Education, training and information

- Co-operation amongst co-operatives

- Concern for community.

They emphasise democracy and shared equity while providing economic and social returns to members and their communities.

For more detail, see the International Co-operative Alliance’s Guidance Notes to the Co-operative Principles (2015). |

Member focus

The co-operative principles focused on members is part of what makes co-operatives unique. Members share in the control of their co-operative and they elect board members, as a rule, from themselves (providing direct influence over strategy and key decisions). Some co-operatives also allow independent board members to be elected/appointed.

Key matters for co-operative boards include:

-

- ensuring the co-operative’s purpose is central to its members and that members are central to strategy development

- promoting the right operating system to build and sustain competitive advantage

- aligning incentives so that governance sits effectively with the wider economic participation of members

- nurturing, securing and retaining allegiance of its members.

The Co-operative Corporate Governance Code (2019) in the United Kingdom is applicable to all types and sizes of co-operatives. Some of the general principles and provisions may be helpful for some New Zealand co-operative board members. |

Getting the rights skills and experiences at board level

Getting the right skills and experience is critical for all boards, but it can be a particular challenge for co-operatives including where elected members have similar backgrounds and expertise. The New Zealand boards and frontier firms report (2020) by the Productivity Commission noted that another challenge is that elected members may be selected for characteristics other than their governance skills.

The International Co-operative Alliance’s Guidance Notes to the Co-operative Principles discusses how these challenges can be addressed:

“The democratic [election] process, by itself, does not guarantee that the board of a co-operative will be competent and have the range of skills and expertise necessary to ensure the proper and effective governance of a co-operative, or have the capacity to hold executives to account. Annual board skills audits are advisable in order to ensure that boards have the collective profile and range of knowledge and skills needed to exercise effective governance control. Where a skills audit identifies gaps in the competence of the board, the gaps may be filled by planned training for board members, by the co-option of non-executive board members with the experience or skills the board lacks, or by positively encouraging members with the skills and expertise needed to stand for election to the board.”

Many New Zealand co-operatives place significant investment into succession planning and professional development. Succession planning can help ensure boards have the right mix of skills, experience and diverse thinking required to lead the organisation. It can also help manage turnover and refreshment of the board. Developing members coming through the pipeline is vital in co-operatives. All board members (and aspiring members) should have access to education and training and be willing to commit to their professional development.

See also the Four Pillars of Governance Best Practice sections 2.4 Board composition and succession planning and 2.8 Director development.

Key considerations for co-operative boards include:

-

- ensuring that there is the right mix of skills, experience and attributes on the board to lead the organisation (including a balance of shareholder directors and independent directors)

- managing the costs of a participative model of governance

- using advisors where appropriate, including on advisory boards

- accessing specialist governance education so board members appreciate the nuances of the business model

- reviewing constitutions to ensure they provide frameworks/guidelines to support diversity of skill sets and rotation of shareholder directors

- disclosing governance policies and practices (eg in the annual report) such as committees and remuneration.

It is critical that shareholder directors are clear about their governance role and responsibilities (including acting in the interests of the organisation) and that they take off their shareholder ‘hat’ when they serve on a board. This includes leaving management to manage the business.

Duties and liabilities

People serving on boards of co-operatives have key duties and responsibilities. These will generally be found in the entity’s rules (constitution), governing legislation, other legislation and case law. The consequences of a board member breaching their duties can be significant. Board members should be aware of relevant legal requirements and expectations.

Access to capital

A particular challenge for a co-operative can be the shareholders’ ability/willingness to provide equity capital. The ownership structure creates challenges for accessing funds from financial institutions (lacking understanding of their capital structures and risk) which also impacts start-up. In order to mitigate this, some co-operatives have created classes of shares to enable the generation of additional funds. As both co-operatives and investors continue to adapt, there is an increased focus on how co-operatives can be funded for further sustainable growth.

A sustainable model

The co-operative model has been around since the early 1800s and the International Co-operative Alliance ensures that the founding principles remain relevant to today’s global environment. The model is highly sustainable and resilient with many co-operatives being at the forefront of innovation in New Zealand and globally.

The 2020 World Co-operative Monitor report (by EURICSE and International Co-operative Alliance) found that the top 300 co-operatives and mutuals report a total turnover of over two trillion USD. |

Cooperative Business NZ is the representative body for New Zealand’s co-operatives. For further information and advice contact info@nz.coop |

[1] International Co-operative Alliance, Guidance notes to the co-operative principles (2015)

[2] EURICSE and International Co-operative Alliance, World co-operative monitor report (2020)