Governance news bites – 30 May

A collection of governance-related news that you might have missed in the past two weeks.

New Zealand is not immune to the environmental and social impacts created by the fashion industry.

Fashion provides a visual reference for moments and events in our collective memory. A signifier of social movements it informs music, literature, painting and advances in technology.

But today fashion is defined by the need for speed, followed by attempts to slow it down. Online shopping has perpetuated our desire for more - fast fashion has put increasing pressure on the supply and demand chain, resulting in a need to address the welfare of garment workers and illuminating the human and environmental cost behind what we wear.

Considered one of the largest polluters in the world, the garment industry accounts for approximately 92 million tonnes of textile waste in landfill each year.

And if you think you’re doing good by donating your clothes to charity, think again.

Your unwanted items could be heading offshore to places like Ghana where it arrives in overflooded second hand markets. Here sellers claw at one another to get their hands on the best bales of clothing. Unsellable items that are ripped, torn, stained or otherwise end up discarded in a city called Accra along a 10-15 metre-high ridge surrounding the perimeter on the edge of a fabric-polluted lagoon.

But despite our size, New Zealand is not immune to the environmental and social impacts created by the fashion industry. Over the past 5-10 years a move towards sustainability has been reflected in established brands like Kate Sylvester offering a repair service for items bought from her range. A ‘Reloved’ section dedicated to finding homes for preloved Kate Sylvester garments also features on the brand’s website.

Likewise, Karen Walker has made a sideways shift to eco-friendly womenswear and produces a small collection of organic cotton blouses and dresses that fit the tone of today’s more timeless simple shapes with a touch of Karen Walker whimsy.

Intermediate designers prove they are committed to slowing the pace of fashion right down with Maggie Marilyn, Wynn Hamlyn and Penny Sage leading the charge with fewer drops and tightly honed collections drip fed to consumers. This creates room for flexibility and contributes to traceable transparency throughout the production process.

And this demand for transparency has been vital since the collapse of Rana Plaza in Bangladesh (2013) where more than one thousand workers lost their lives and around 2.5 thousand were injured in the eight-storey building.

But other events have impacted the industry since then. The onset of COVID-19 has provided substantial challenges for the fashion industry here and abroad. With global resources on hold or out of reach, those in the fashion industry have had to find ways to continue running their businesses.

Gosia Piatek is the founder of ethical and sustainable clothing label Kowtow and says during Covid the reduction and competition in sea freight caused longer delivery times. The brand’s manufacturing process is already slow and runs to an 18-month production schedule, yet the logistical delays have still been felt by the brand.

Kowtow has been running for more than a decade and is based out of Wellington, manufacturing through a Fairtrade supply chain in India using only locally sourced 100% organic cotton. Kowtow garments are sold through international stockists including Europe, USA, Australia.

By the end of 2020 when New Zealand had already come out of its first lockdown, Piatek made the decision to establish an advisory board. The idea followed long-term strategy work that Kowtow had been doing with NZTE and Deloittes.

Having an advisory board to call on when larger issues are at hand means Kowtow is in a better position to remain dynamic while future proofing and developing the business.

“To keep up with the changing needs of our business and this vibrant industry we wanted a board that had flexibility and would evolve,” she says of choosing the advisory board model.

Continuing to stay on a sustainable trajectory which spans the entire business was also essential. Kowtow’s ethos and purpose – to use clothing as a vehicle for positive change where people and the planet come before prosperity – also translates through its governance model.

“With [our] vision to leave the planet better than we found it and thread our ethics into everything we do, bringing on an Advisory Board of think-minded, purpose driven people was crucial to us,” says Piatek who sums up sustainable governance as a reflection of the best of the environment.

“It's dynamic, challenging, resourceful, caring and brave - governance with a global view that recognises and acts on this still allows business to grow and make the planet better for us all.”

Making the planet a better place, or at least having an awareness of the damage that has been done and looking for ways to repair it is a top priority. The advantage for locally made brands is the ability to produce smaller runs which will also have less impact on the environment.

But unlike Kowtow, many in the fashion industry are not in a position to establish their own advisory boards due to their size, and independent businesses have been fending for themselves in the fashion wilderness - albeit, immaculately dressed.

A tension for the local industry, establishing an industry voice has been a struggle until now.

Mindful Fashion is an incorporated society run by a board of directors with the aim to provide practical advice and solutions to anyone in the New Zealand fashion industry.

Established in 2019 by Kate Sylvester and Emily Miller-Sharma (Ruby), the organisation was founded as a response to the Tear Fund Ethical Fashion Report (2018). That year a handful of leading New Zealand fashion brands were poorly ranked which left many Kiwi designers scrambling for cover amidst a finger-pointing frenzy that saw some subjected to heavy media scrutiny.

Jacinta Fitzgerald is a fashion sustainability strategist and programme director for Mindful Fashion. She says Kiwi labels were ranked against much larger corporate companies and the structure of the survey did not fit a New Zealand context.

Mindful fashion programme director, Jacinta FitzGerald

“[In New Zealand] we need to take a much more bespoke approach because our supply chains are different,” she says.

That year the benchmark was set so low that bigger companies operating on fast fashion models with known issues in their supply chain – including not paying a living wage – were scoring top marks, leaving some Kiwi brands with much lower grades. Conflicting with this grading system, many Kiwi designers often do much smaller production runs and work in close proximity with their suppliers, having a traceable and transparent process from start to finish.

Mindful Fashion currently has around 70 members and holds education workshops and forums.

Co-founder Emily Miller-Sharma says it enables smaller independent businesses to come together and approach fabric suppliers as a collective, giving them greater purchasing power which leads to other sustainable initiatives.

“There is actually no other option than working together and the more we know, the better the entire industry is going to be,” she says.

But initially the prospect of working collectively met with some resistance. The more established businesses were used to protecting their suppliers.

“Kate Sylvester and [Managing Director] Wayne Conway helped me understand that when they were first starting out as designers, it was really difficult to get fabric suppliers [because] the factories didn't want to deal with these designers because the accounts were too small.”

For many years, Kiwi brands were able to protect their intellectual property through developing their relationships with suppliers, ensuring no one else could get their hands on the same fabric.

“In order to get a red knit, you were only really able to go to a certain supplier. Whereas now, it's very easy to source infinite shades of red. It's a completely different world, but that’s the thing about shifting culture, unless there's a reason to change, you just don't.”

Ruby GM, Emily Miller-Sharma says sustainability is nuanced

Also a member of Mindful Fashion’s board of directors, Miller-Sharma says when Covid arrived on New Zealand shores one of the challenges for the industry was selling to customers under new restrictions which prevented customers from trying garments on. As a necessary part of the purchasing process that was not viable for makers.

Mindful Fashion were able to speak out on behalf of the industry and that rule was subsequently changed.

The board for Mindful Fashion is led by James Walker who is one of the few directors with no connection to the fashion industry. Miller-Sharma sees that as an asset.

“He can properly listen and see the potential outcomes by thinking through the different scenarios that may or may not happen.”

Some of the top priorities on the agenda are to raise the entire industry's sustainability status. And next is to ensure the organisation adds value to the industry.

“We have an education working group which includes our educators, designers, manufacturers and fabric suppliers who come back to the board. Then the board is able to consider something that is truly of the industry and ensure that it's still in line with the entire vision of Mindful Fashion,” says Miller-Sharma.

Another major concern is a labour shortage in specialist areas which includes cutting and pattern making. Many in these roles are soon due for retirement and with fashion institutions focussing on design, there is no one left to replace them.

“There's no actual career map in terms of the fashion industry and if we want to continue to have a New Zealand made product we need to have support,” she says of Mindful Fashion’s goal to put provisions in place and ensure students are aware of the multitude of roles available across the industry.

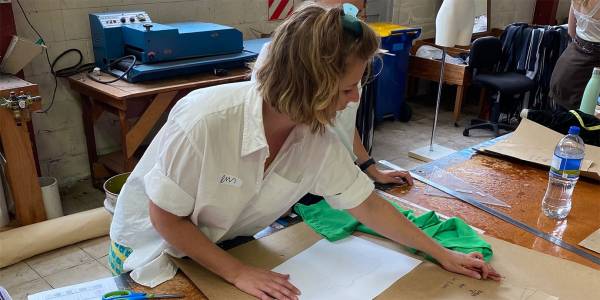

Emily Miller-Sharma in the Ruby workroom

Building and sustaining a business is as much about upholding brand reputation as it is about keeping the financial side ticking along. But there have been times where the fashion industry has been thrust into the media spotlight, which for many designers, instils a bit of fear.

“When I first used to do interviews, I wouldn't be able to sleep. It would be so stressful because it was just like, what if I said the wrong thing and what if it's taken the wrong way?” says Miller-Sharma.

The other challenge is breaking down outdated perceptions that shroud the industry and see it as vain or superficial.

“I think it's really important that as businesses, we do what we can to challenge that [because] the industry is made up of people who just really like working with fabric, are really good at working with their hands and are highly skilled,” she says.

Mindful Fashion aims to strengthen the longevity of New Zealand Made and Miller-Sharma says it has helped neutralise the conversation when issues arise.

She says some designers feel like they are not doing enough and others are scared of claiming they are doing more than they say they are. There is also a fear of being exposed, as in the case of Kiwi fashion brand, WORLD, in 2018 who were importing sequin motifs from Ali Express.

As a collective, Mindful Fashion provides a safe platform for those in the industry to speak up.

“It exists purely to ensure that we have a sustainable thriving industry. Sustainability is so nuanced and there are real challenges,” Miller-Sharma says.