Seize the power

The lower unit costs of self-generated electricity will save your business money, if you do it right.

Climate-related disclosure requirements for major financial institutions will have wider impacts on banking and insurance customers, including reporting on their greenhouse gas emissions. As a result, directors need to be aware of quiet revolution around climate change opportunities and risks that this will drive.

We have all heard the increasingly urgent calls for action on climate change from scientists, business leaders, investors, consumers and stakeholders alike. Societal expectations, along with recent legislative developments, means there is a growing expectation on organisations:

In light of this, the financial sector has been reconsidering the products it sells and its investing practices and policies to take into account the effects of climate change. Its response to climate change will have a far-reaching impact on many other businesses who bank or insure with these organisations. Addressing climate change within your organisation is no longer simply a “nice to have” but is quickly becoming a standard expectation for all organisations, and boards and directors need to be ready.

Large financial services institutions have for some time been considering the effects of climate change and are generally committed to actively managing the environmental impact of their activities. This includes not only their own environmental impacts from their day to day operations and within their own supply chains, but also their approach to business lending and insurance.

Central banks (both internationally and in New Zealand) have traditionally been considered by many to be rather staid or stuffy in their approach and yet even they are now thinking about the impacts of climate change. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand (RBNZ) has set out its approach to climate change. It identifies climate change as a direct challenge to financial stability, with its main concern being the exposure of the financial sector to climate-related risks. RBNZ’s Statement of Intent 1 July 2020-30 June 2023 acknowledges the critical risk posed by climate change and states it will work to assist the transition of the New Zealand economy to a low carbon future.

It is intending to conduct a full scenario-based industry climate change stress test in 2023 and will “promote banking sector climate change capabilities by increasing supervisory intensity on entities that are not positively progressing their climate change capabilities”.

Business customers can increasingly expect to see banks and insurers monitoring the social and environmental risks of their own customers and asking their customers to demonstrate to them how they are managing and mitigating their own environmental impacts. So far banks have been engaging with customers to help them understand their climate related risks and opportunities and the changes they could make in order to address and mitigate their risks. For some of the largest emitters this work has been ongoing for a number of years already. Businesses in high-emission sectors in particular, can expect increasing interest from banks in their climate impact and actions they are undertaking. If not taken seriously enough, businesses may find their cost of capital increasing and their customers shifting away to more environmentally conscious competitors. There may even come a time where businesses in some sectors may not be able to obtain lending from a bank. In a recent news article ANZ, the country’s largest bank, indicated they may exit relationships with their customers if they could not see a willingness to engage on climate change issues from a customer.

This interest is being accelerated by the recent introduction of a mandatory climate-related disclosure framework in New Zealand. The Financial Sector (Climate-related Disclosures and Other Matters) Amendment Act 2021 is a world first and makes it mandatory for approximately 200 ‘climate reporting entities’ under the Act to produce climate statements in accordance with disclosure requirements set out in the External Reporting Board’s (XRB’s) standards. ‘Climate reporting entities’ or ‘CRE’s’ under the Act are:

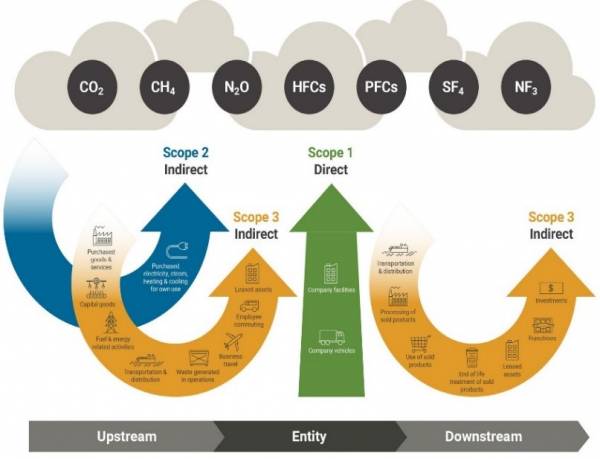

The XRB aims to issue its first climate standard in December 2022, meaning CREs would be required to make disclosures from early 2024 (at the earliest) for annual reporting periods starting on or after 1 January 2023. While there are only approximately 200 CRE’s captured under the Act, the impact of the mandatory reporting will be felt by many more organisations, particularly because the standards require disclosure of all scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions (GHG emissions). These are indirect emissions, not covered in scope 2, that occur in a CRE’s value chain, including both upstream and downstream emissions (see Figure 1).

For the financial sector this includes all financed emissions. With only a very small percentage of businesses having accurate emissions data publicly available, collecting this information poses a significant challenge for the financial sector.

ASB is currently examining various options to address this issue. One standard it is exploring is the international Partnership for Carbon Accounting Financials (PCAF) which provides a methodology to calculate the emissions that can be attributed to loans and investments. ASB has also identified business customers it estimates to be among the highest emitters in its portfolio, and has started engaging with them to understand not only their carbon footprint, but also how these companies are approaching sustainability and what support they require.

Miranda James, Head of Corporate Responsibility at ASB, says there is a range of maturity in terms of customers’ sustainability progress and consequently, the availability of accurate emissions data is variable. “Our analysis shows that emissions in our corporate lending portfolio are likely to be concentrated in a small number of large companies. That is quite different to the rural portfolio for example, where a large number of customers collectively make up the emissions profile. One of the challenges for us, is how we can engage with smaller businesses in a way that is proportionate and doesn’t create a data challenge they are not yet equipped to meet.”

The financial sector is not just concerned with a business’s carbon footprint however. Banks are looking to work with customers that support social and environmental sustainability. They are wanting to understand what a business’s climate transition risks and physical risks look like, the opportunities that may arise, and how they are managing their environmental impacts. For example, if you are a business that supplies a large corporate with a low carbon procurement policy, are you doing enough to compete? Do you have a good enough story around the sustainability of your business and product to compete and attract staff? What are your physical risks? For example, if you rely on raw product inputs, how might they be affected by natural disasters? In addition financial institutions will be asking what plan is in place to mitigate or adapt to these risks and what is the capability within the business to manage and govern the organisation through these issues?

Another important and evolving area for banks is sustainable lending. Many banks, including ASB, have a climate change strategy that includes a commitment to support the transition to a low emissions economy and banks already provide millions of dollars a year in sustainable lending to New Zealand businesses. ASB recently lent Hawkes Bay Airport (under the Reserve Bank’s Funding for Lending programme) $23m to help support its goal to become NZ’s most sustainable airport and Craigmore Sustainables (a company with a portfolio of dairy, grazing, forestry and horticultural properties) has received $78m in funding to be put towards its work in land-based reduction in greenhouses gases. Transition financing such as ASB’s low carbon asset financing can also help high emitting customers transition to low carbon assets. This type of financing has supported one ASB customer in the tourism sector, for example, to transition from petrol camper vans to a fleet of hybrids.

Insurers are also paying close attention to how their customers are identifying, managing and mitigating their environmental risks and impacts. In the paper D&O insurance – a rising sea of change, jointly published by the IoD, Dentons Kensington Swan and Marsh, it states: “The advancement of climate-related disclosures will also drive broader ESG disclosures from organisations. The requirements for additional disclosures can increase the potential for directors to be held liable for wrongful acts when those obligations are not met, and potentially claims that may be covered under D&O insurance. Insurers are therefore increasingly focusing on ESG metrics and disclosures when assessing risks.”

Generally speaking organisations globally are under increasing pressure to demonstrate their commitment to transitioning to a more sustainable economy and failing to do this exposes them to risk. To help companies assess their ESG performance, Marsh McLennan, a global leader in risk advising and insurance broking, has developed an ESG Risk Rating Guidance document. This provides a framework, developed with a risk and insurance lens, for organisations to understand how their ESG performance may be perceived and to help communicate it to potential insurers. The framework includes 18 key areas of ESG focus, as defined by international standards and frameworks. It includes 20 questions on climate change relating to the company’s net zero transition ambition, energy mix, emissions intensity disclosure, alignment with national and international targets and questions about how the company considers climate change in its long term planning. There is also a focus on the organisation’s governance strategy and the effectiveness of its governing body in relation to ESG issues.

There are plenty of examples of New Zealand businesses, both large and small, who have already undertaken extensive work to understand their climate related risks and opportunities and who are actively working to mitigate and manage those risks. For many of them doing business sustainably forms a core part of their values. In the Institute of Directors’ Director Sentiment Survey 2021 48% of respondents agreed that their board was engaged and proactive on climate change risks and practices in the business.

However, there are many businesses, especially those smaller and medium sized businesses, who do not have the resources, capabilities and understanding that will soon be necessary to respond to the increasing expectations of their consumers and other stakeholders, including potentially their own financers and insurers. This could become a significant problem for some if the cost of financing or insurance becomes prohibitive or restricted in some way as a result. Recent discussions with two Nelson food exporters revealed their business owners are increasingly aware of the need to address climate change within their organisations. While they had already taken some measures in this regard, neither of them had an overall climate change strategy for the organisation in place and both acknowledged this was something they did not have the resource or expertise to produce themselves.

Venus Sood Guy is the Operations Manager at New World Nelson. She also sits on the boards of the Nelson Tasman Chamber of Commerce and Abbeyfield New Zealand (a registered charity); and is the chair of Nelson Tasman Kindergartens. While Foodstuffs NZ already has a comprehensive climate change strategy in place, Venus believes that, generally speaking, there is not enough awareness amongst smaller businesses about the level of reporting that may be required from them in the future. “All the businesses I have been talking to, they are all taking small steps towards being more environmentally friendly. But the last three years have been hard on them. Their focus has been on dealing with the pressures of Covid and lack of staffing and they haven’t had the time or resources to properly address the impact of climate change on their business.” This challenge is likely to be even harder for charities and not-for-profit organisations, who are even less likely to have the funds or resources to address this. “Nelson Tasman Kindergartens are all taking small steps towards operating in a more environmentally friendly manner, and we have made a commitment over a number of years to both facilitate and undertake a large investment of time and resources into the Enviroschools Programme” says Venus “but there is currently a lack of resource or funding within the organisation to properly address this. However this is something that the board will need to consider going forward.”

New climate related disclosure regulation, increasing scrutiny on large corporates and the public sector, including banks and insurers means these organisations will be looking to do business with smaller organisations that can demonstrate they are addressing and mitigating climate change. It is foreseeable that businesses wanting lending and insurance in the future may be asked to provide their climate change risks, strategies and opportunities to their banks and insurers, in the same way as they will be asked for their annual financial statements. Businesses need to ensure they have the right strategies, systems, processes, policies and capabilities in place to respond. Many boards in New Zealand are already taking action on addressing change, but for those that have not, climate change will need to become an urgent priority on the board agenda.

Regardless of whether an organisation is required to report under the new mandatory disclosure regime, it is becoming clear that how an organisation manages climate risk is something banks, insurers, consumers and other stakeholders are becoming increasingly interested in.

Following governance best practice, there are a number of things directors and boards need to consider including: